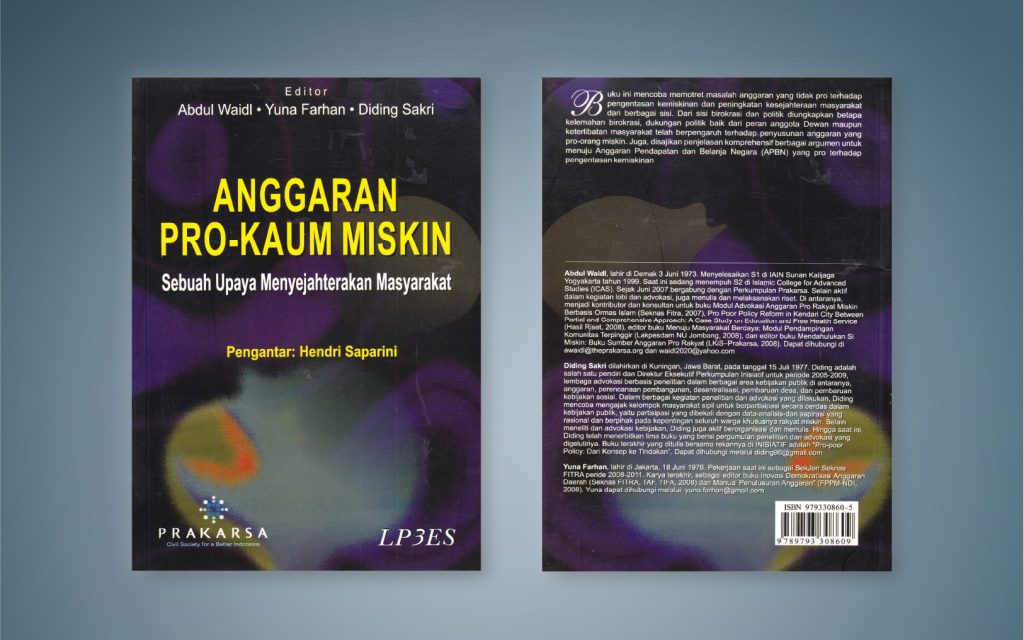

Abdul Waidl, Yuna Farhan, Diding Sakri (editors)

ISBN 978-979-3330-86-0

Introduction : Hendri Saparini

LP3ES Library Publishers and Associations PRAKARSA

First Printing, December 2009

xxvi + 339 pages ; 15,5 x 23 cm

Shows on television about young fathers and mothers who use their wheelbarrows as a means of earning a living as well as a home to raise their children, as well as stories of parents who are forced to let their children share in earning a living because they cannot afford to send them to school, we see more and more often. Not to mention the news about the increasing number of sufferers of malnutrition and the poor who find it difficult to get clean water or other public services, which seem to never end. Of course we agree that the widespread coverage of various life problems faced by the poor is not just the fruit of press freedom, but the number of poor people is still very large.

It is very ironic that after Indonesia has been developing for more than 63 years and has drained various natural resources, it has resulted in a deeper socio-economic gap. A small group of people live very well off, are able to get the best education, very high quality health facilities, very decent jobs, live in a luxurious environment with number one public facilities, etc.; but on the other hand there are still tens of millions of Indonesian people whose level of welfare is still far behind. Far from accessing education, health, employment, and proper public service facilities, many people cannot get it for food, clothing and decent housing.

One of the proofs, in the 2008 APBN it was budgeted that as many as 19,2 million Indonesian families were eligible to receive Raskin (rice for poor families), meaning that there were around 50 million people who still needed rice assistance. In practice it turned out that there were far more of them than had been budgeted for, so the rice ration of 10 kg per family per month had to be reduced so that it could be distributed more evenly. In addition to various weaknesses in administration, the increasing number of poor families is a result of the increasingly heavy burden on the lower classes of society. Poor and limited services for basic needs which should be public services, currently must be borne by the community, such as the cost of education, transportation, health, etc.

Role of Government Through APBN

One of the powerful weapons that the state has to ensure the welfare of the people is through a budget policy that regulates sources of revenue and government spending policies. The preparation of plans, implementation and monitoring of the budget carried out jointly by the Government and the DPR should make the State Revenue and Expenditure Budget (APBN) a powerful tool towards a more just development. This means that the bigger the APBN, the more evenly distributed the development is for all the people.

Moreover, the 1945 Constitution has mandated the state to carry out development with the aim of maximizing the prosperity of the people. This objective has been expressly stated in the Preamble to the 1945 Constitution and the articles in the 1945 Constitution, both the original and the amendments. Article 23 paragraph 1, for example, clearly states that the APBN must be used for the welfare of the people. There are still many articles in the constitution that clearly regulate the rights of the people and the duty of the state to create prosperity for all people; regarding the management of the economy and natural resources for the greatest prosperity of the people; the mandate that the poor and neglected children be cared for by the state; people's rights to education, health, employment, etc.

The constitution has regulated what is the right of the people from various state revenues managed by the state and firmly determines the obligations of the state in fulfilling people's rights from the management of the State Budget. Supposedly, the greater the volume of the government's budget, the greater the government's capacity to carry out the constitutional mandate to bring people more prosperity, but that is not the case.

As an illustration, the APBN increased rapidly from IDR 380 trillion (2004) to around IDR 980 trillion (2008). However, the development results obtained during this period were not comparable. For poverty alleviation, for example, although the poverty budget increased sharply from IDR 18 trillion (2004) to around IDR 70 trillion (2008), the number of poor people has not decreased significantly. If in 2004 the number of poor people was 36 million people, then in 2008 it remained at 35 million people. In fact, the number of poor people is likely to be even greater if the survey was conducted after the increase in fuel prices in May 2008.

Role Through Pro Poor Policy

Strategies to improve people's welfare require macroeconomic policies that are oriented towards poverty alleviation and improving people's welfare or pro-poor macroeconomic policies. Of course, policies must be carried out thoroughly/comprehensively both in fiscal and monetary policies as well as in industry and trade.

Fiscal policy. If poverty and unemployment eradication programs become development priorities, then as a consequence the government is required to have a pro-poverty eradication and job creation (pro-job) fiscal policy. In the preparation of state revenues, for example, ways to increase revenues should not be counterproductive to efforts to eradicate poverty. Budget savings by removing people's subsidies should be the last resort after the government has taken various other policy steps.

Likewise, efforts to increase revenue from tax sources should be avoided from policy choices that will have a direct impact on poor people. The growth of direct taxes (direct taxes) such as PPh must be prioritized over indirect taxes (indirect taxes) such as sales taxes, etc. because they will have a direct impact on the poor. Policy reforms must also be carried out regarding government revenues from the management of oil and gas and mining natural resources, such as: renegotiating mining contracts which so far have only provided minimal benefits for the people or measures to securitize oil and gas resources must be a priority alternative.

On the expenditure side, spending allocation policies should prioritize expenditures that will have a positive impact (multiplier effect) on reducing poverty and unemployment. Submitting a debt write-off or debt limitation must be a strategic step that is carried out in earnest to reduce the burden on the state budget. However, these alternatives will never emerge if the neoliberal paradigm underlies budget management. Economic stimulus that requires the support of a large development budget, for example, is very difficult to do because this step is contrary to the concept of a conservative paradigm. The spending budget is trying to be very tight. Efforts to seek financing by writing off debt, limiting the use of the budget for debt repayments, renegotiating mining contracts or oil and gas securitization, will also not be an option because they are contrary to the paradigm adopted.

Monetary policy. As with the management of fiscal policy, monetary policy must also be pro towards solving poverty and unemployment. Failure to manage macro policies, such as in controlling prices, is also the cause of declining public welfare. In 2007-2008, the inflation rates for foodstuffs were 11,3 and 13,5 percent, much higher than the general inflation of 6,6 and 9,4 percent. With just an overview of the burden of food inflation, it can be concluded that the purchasing power of the grassroots will be trimmed by inflation. As is well known, 70 percent of the expenditure of the poor and near-poor is used to meet food needs. Especially if you take into account the results of BPS and ADB surveys which concluded that the inflation faced by the poor is 2-3 times the national average. It is increasingly clear that the welfare of the grassroots will continue to decline and the gap will become even sharper without policy reforms and the government's role.

Inflation control can be carried out through monetary policy or real sector policy. Inflation problems in Indonesia are mostly caused by problems in the real sector, however, with a conservative and monetarist economic paradigm (focus on monetary policy choices), inflation is more often dampened by monetary policy. This policy choice error is clearly counter-productive to alleviating poverty and unemployment. High interest rates have a negative impact on people's purchasing power and production costs. This double pressure (double pressure) is what ultimately drives big layoffs. Even if the government takes policy steps in the real sector, the main focus is more directed at monetary rescue. So often ignore the negative impact on the real sector.

Trade and industrial policy. Sectoral policy priorities greatly determine the quality of growth in alleviating poverty. In recent years, Indonesia's economic growth has been supported more by growth in capital-intensive and high-tech economic sectors. Policy orientation that prioritizes the speculative sector ultimately reduces growth in the real sector. As a result, the absorption of labor resulting from economic growth is getting lower.

As an illustration, in the 2005-2009 RPJM the target for job creation per 1 percent of economic growth was 450.000 workers. However, Sakernas data for 2005-2006 noted that the number of net jobs that could be provided per 1 percent of economic growth experienced a very significant decline. If before 2004 the net absorption of 1 percent of growth could reach 240.000-250.000 jobs and in 2004 decreased to below 200.000, then in 2005-2006 the absorption of economic growth was only around 40.000-50.00040.000 50.000-1 jobs per XNUMX percent growth. The decline in the quality of growth occurs because current economic growth is not supported by high growth in labor-intensive sectors such as the agriculture, industry and trade sectors but the financial and telecommunication sectors which are very capital intensive.

The unprepared choice of agricultural liberalization policies also resulted in a decline in the welfare of farmers. This condition is very different from countries that still believe in the importance of a broad government role. European countries or Japan put a strategy to develop the agricultural sector by taking various steps to save it from the wave of liberalization. Indeed, at this time it is very difficult to carry out a tariff war policy (tariff barrier). However, there are still many other policies to support the agricultural sector. For example, the big role of government is indicated by large government spending to support the competitiveness of farmers' products.

The intensive policy of trade liberalization has further suppressed the competitiveness of local products in the domestic market through a flood of legal and illegal imported products. Liberalization of the trade and industrial sectors also has an impact on labor in alleviating poverty and unemployment. In the garment sector, currently 77 percent of the domestic garment market is dominated by imported products, 70 percent of which are illegal products. The decision to export raw rattan, for example, had a major impact on the bankruptcy of the rattan furniture industry in Cirebon and Sidoarjo which ultimately prompted a wave of layoffs.

Consistency PRAKARSA

During this 'Association PRAKARSA' has always been consistent in supporting the realization of a pro-poor APBN, which until now has not been realized. The anxiety was finally poured very well in this book. This study attempts to portray the problem of budgets that are not pro-to poverty alleviation and improvement of people's welfare from various perspectives. From the bureaucratic and political side, it was revealed how the weakness of the bureaucracy, political support from both the role of members of the House and the involvement of the community have influenced the formulation of a budget that is pro-poor.

This book presents a very comprehensive explanation of the various arguments towards pro-poverty alleviation APBN. In the budget allocation strategy, the argument that a pro-poor budget must be related to long-term social sector development is very interesting. So far there seems to be a separation. Even with the tendency of the government to shift the responsibility for basic infrastructure development to the community through various independent programs such as PNPM Mandiri. With PNPM Mandiri funds, the community may use it for health services, provision of basic facilities such as clean water, education, road construction, etc. Very large funds (in 2007 it will reach Rp. 77 trillion) should not be used for short-term programs. Provision of supporting infrastructure such as roads, transportation, clean water, education, health, should be the responsibility of the government and implemented with integrated and centralized planning so that it is more effective and will provide long-term social and economic benefits.

Another important discussion is about the pro-poor budget which must be planned properly not only in selecting program allocation priorities but also in choosing a development financing strategy. Currently, the attention of the public, including members of the Council, is more concentrated on the allocation strategy, not on financing. In fact, as stated in this book, the wrong financing strategy will create a burden for society in the future. The discussion on taxes and financing alternatives is very important. It turns out that there are financing alternatives that are more equitable and focused so as to ensure that the financing is really for financing infrastructure development and poverty alleviation.

Finally, we congratulate the authors for providing very useful information. This book will be very useful for members of the DPR, the Government and the general public because it is able to explain and provide extensive arguments about the importance for Indonesia to immediately realize a pro-poor budget to reduce disparities and deepening poverty.

Part One:

Highlighting Key Problems Pushing Pro-Poor Budgets in Indonesia

---------

- The Pro-Poor Budget: Concepts and Practice

- Fiscal Policy After the Crisis Judging from a Pro-Poor Budget Perspective

- Monetary Transmission Without Fiscal Driver

- The Role of Parliament in the Budgeting System in Different Countries:

- Budget Bureaucracy Politics in Indonesia

- Perception Mapping Study on Pro-Poor Budgets in Indonesia

Part Two:

Exploring Solutions to Achieving Pro-Poor Budgets in Indonesia

---------

- Optimizing State Revenue for National Development Financing

- ORI Focused: Fiscal Stimulus Toward Fully Working Economic System

- More Significant Education and Health Spending

- Creating a DPR and Parliamentary Support System that Supports Pro-Poor Budgets

- CSO Working Group Strategy and Budget Committee Strengthening